Someday, it will bring humans together and drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But – lest we verify our daydreams so meticulously here – how exactly will global temperatures respond to that day? This is a question that climatology has always worked to answer, although the demons in the details have led to some confusion.

A new study led by Chen Chu of Nanjing University tracks down and displays another demon. Research is increasingly showing that not only the average surface temperature of the planet is important for tracking warming, but the spatial pattern of these temperatures. This can be important to account for things like climate sensitivity to greenhouse gases, but it has not been taken into account in some methods of estimating how emissions reduction affects warming.

See a pattern

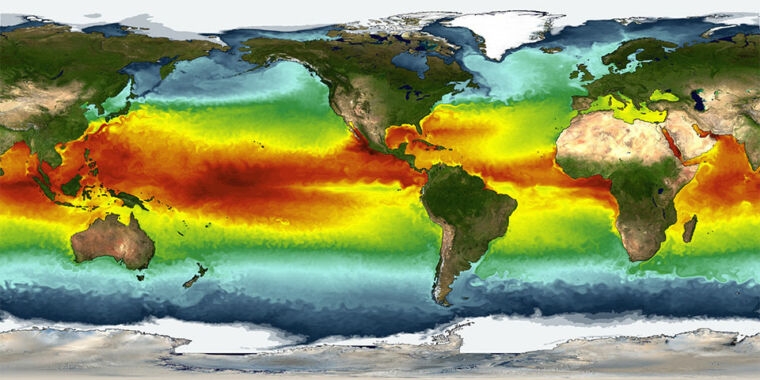

The “pattern effect” of warming in different regions of the globe affects the way the planet drops heat back into space. For example, if warming is slightly stronger in the tropical western Pacific Ocean – which it is – this region is better at producing a reflective sun cloud cover and releasing heat upwards. If you assume that warming is occurring evenly around the world, you would lose this compensated behavior a little.

Building on previous work, the researchers calculated the effect of the pattern on today’s world by comparing historical observations with simulations of climate models of pre-industrial climate. Then they tested the pattern’s effect numbers using satellite measurements of the Earth’s total energy balance over the past few decades. With no effect on the pattern, the estimated accumulation of energy in Earth’s climate runs slightly higher than satellite measurements. But mixing the pattern effect numbers yields predictions that match measurements well, including year-to-year vibrations.

What does this mean for a low-emissions future? One way to calculate this was to use the observed human-induced enhancement of the greenhouse effect and past temperature change. Based on a calculation of Earth’s sensitivity to climate, you can then ask how much warming should happen once the greenhouse gases stop increasing. Since the climate (mainly oceans) cannot be equilibrated immediately to a stronger impact of global warming, temperatures take some time to catch up completely.

But where will you be once you catch up? If the pattern effect dampens the previous ground response, there could be more pipeline warming – and a warmer end result.

Fear of commitment

The calculations of warming we are already committed to critically depend on assumptions about what our future emissions will look like – a major source of confusion. The scenario used in this paper is one in which we reduce emissions enough to maintain current greenhouse gas concentrations. They are no longer rising, but they will not descend either. In this simple scenario, the climate system gets a chance to catch up and reach a new equilibrium. However, this is not a file zero An emissions scenario, where we cut off all emissions and greenhouse gas concentrations begin to slowly decline as the Earth absorbs them.

With this in mind, the results show that calculating the effect of the pattern should increase the bound warming. For concentrations to stabilize at 2020 levels, if we wait centuries for temperatures to equilibrate, the overall warming since pre-industrial times grows from about 1.3 ° C to 2.3 ° C. (We have so far experienced a temperature rise of around 1.1 ° C.)

An alternative version of this scenario allows for short-lived gases and particulate matter to vanish; Here the maximum temperature rises from 1.6 ° C to 2.8 ° C. Restricting this long-term view to only the year 2100, the warming grows from 1.3 ° C to 1.8 ° C when calculating the pattern effect.

The exact numbers aren’t really the point here – the researchers note that using a different dataset of past ocean temperatures causes the differences to diminish. It’s the overall finding – having a pattern effect implies more committed warming – is potentially significant. It could mean that if you really want to permanently limit warming to a specific goal, like 1.5 ° C or 2 ° C, you need to err on the side of lower emissions (or plan to effectively remove more CO2)2 Later).

But this should not trigger the fear that more global warming has suddenly become inevitable. The fixed-concentration future differs from the zero-emissions future, and final temperatures only reach very long time horizons. The study’s real contribution is to address deficiencies in some of the methods of computing committed warming. First, we must demonstrate a commitment to stopping global warming if we are to make any of these scenarios – or better – of a future that we can choose from.

Nature of Climate Change, 2020. DOI: 10.1038 / s41558-020-00955-x (About DOIs).

“요은 베이컨과 알코올에 대한 전문 지식을 가진 닌자입니다. 그의 탐험적인 성격은 다양한 경험을 통해 대중 문화에 대한 깊은 애정과 지식을 얻게 해주었습니다. 그는 자랑스러운 탐험가로서, 새로운 문화와 경험을 적극적으로 탐구하며, 대중 문화에 대한 그의 열정은 그의 작품 속에서도 느낄 수 있습니다.”