- Astronomers recently discovered the fastest spinning and possibly the smallest magnetic star known.

- This object, known as J1818.0-1607, is about 21,000 light-years away in Milky Way The galaxy.

- Magnetic stars are a special class of neutron stars that possess extremely strong magnetic fields.

- The researchers used Chandra and other telescopes to identify the unusual properties of this object.

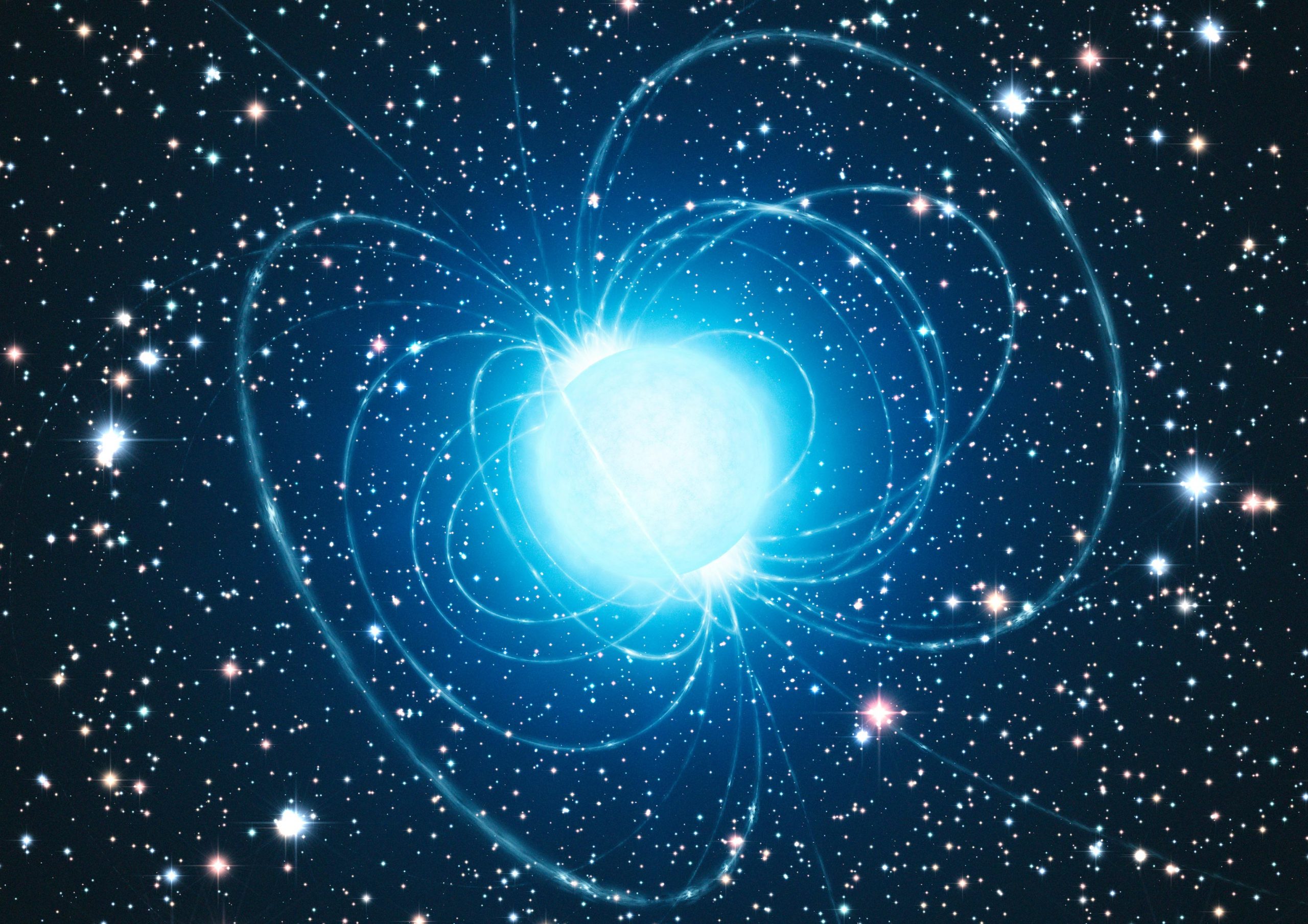

This image contains an exceptional magnetic star, which is a type of neutron star with extremely strong magnetic fields. Astronomers have found evidence that this object may be the smallest known magnetic star (about 500 years in Earth’s time frame). It is also the fastest that has been detected so far (spinning around 1.4 times per second). This image shows the X-ray magnetic star from Chandra (purple) in the center of the image in conjunction with the Spitzer and WISE infrared data showing the wider field of view. Magnetic stars are formed when a massive star runs out of nuclear fuel and its core collapses in itself. X-ray credit: NASA / CXC / University of West Virginia / H. Blumer. Infrared (Spitzer and Wise): NASA / JPL-Caltech / Spitzer

In 2020, astronomers added a new member to an exclusive family of UFOs with the discovery of a magnetic star. New notes from NASAThe Chandra X-ray Observatory helps the observatory support the idea that it is, too Pulsar, Which means that it emits regular light pulses.

Magnetism is a kind of Neutron star, An incredibly dense body consisting mainly of tightly packed neutrons, which form from the collapsing core of a massive star during a supernova explosion.

What distinguishes magnetic stars from other neutron stars is that they also have the strongest magnetic fields known in the universe. For context, the strength of our planet’s magnetic field has roughly one Gauss value, while a refrigerator magnet measures about 100 Gauss. On the other hand, magnetism possesses magnetic fields of about one million billion gauss. If the magnetic star were one-sixth of the way to the moon (about 40,000 miles), it would wipe data from all credit cards on Earth.

On March 12, 2020, astronomers discovered a new magnetic star using NASA’s Nel Girells Swift Telescope. This is the 31st known magnetic star, out of nearly 3,000 known neutron stars.

After follow-up observations, the researchers determined that this organism, called J1818.0-1607, was specific for other reasons. First, it may be the smallest magnetic star known, with an estimated age of about 500 years. This depends on how quickly the rate of rotation is slowing down and assuming he was born spinning faster. Second, it is also spinning faster than any previously discovered magnetic star, spinning about once every 1.4 seconds.

Chandra’s observations of J1818.0-1607 were obtained less than a month after the discovery with Swift, giving astronomers the first high-resolution display of this object in X-rays. The Chandra data revealed a point source where the magnetar is located, and it is surrounded by a diffuse X-ray emission, possibly caused by X-rays reflected off dust in its vicinity. (Some of this diffuse X-ray emission may be due to wind blowing away from the neutron star.)

Harsha Bloomer of West Virginia University and Samar Safi Harb of the University of Manitoba in Canada recently published results from Chandra J1818.0-1607’s notes in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Same as above picture for the exceptional magnet, but marked with J1818. X-ray credit: NASA / CXC / University of West Virginia / H. Blumer. Infrared (Spitzer and Wise): NASA / JPL-Caltech / Spitzer

This composite image contains a wide infrared field of view from two NASA missions, the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Wide Range Infrared Scan Explorer (WISE), that were captured before the magnetic star was detected. The X-ray of Chandra shows the magnet in purple. The magnetic star is located near the plane of the Milky Way Galaxy about 21,000 light-years from Earth.

Other astronomers also observed the J1818.0-1607 using radio telescopes, such as the Karl Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) of the National Science Foundation, and determined that it emits radio waves. This means that it also has properties similar to that of a “spinning pulsar”, a type of neutron star that emits beams of radiation that is detected as repeated pulses of emission as it rotates and slows down. Only five magnetic stars, including this one, have been recorded to also function as pulsars, making up less than 0.2% of the known neutron star cluster.

Close-up of the exceptional magnetic star, J1818.0-1607. Credit: X-ray: NASA / CXC / University of West Virginia / H. Blumer. Infrared (Spitzer and Wise): NASA / JPL-CalTech / Spitzer

Chandra’s notes may also provide support for this general idea. Safi Harb and Bloomer studied how efficiently J1818.0-1607 converted energy from decreased rotation into x-rays. They concluded that this efficiency is lower than that normally found for magnetic stars, and is likely within the range found for other spinning pulsars.

The explosion that created a magnetic star at this age was expected to have left a detectable debris field. To search for supernova remnants, Net Harb and Plumer looked at X-rays from Chandra, infrared data from Spitzer, and radio data from VLA. Based on Spitzer and VLA data, they found possible evidence of a remnant, but at a relatively large distance away from the magnetar. In order to cover this distance, the magnetar must have traveled at speeds far exceeding those of the faster known neutron stars, even if we assume it is much older than expected, which would allow for more travel time.

Reference: “Chandra’s Notes of Newly Discovered Magnet Swift J1818.0–1607” Posted by Harsha Bloomer and Samar Safi Harb, 26 Nov 2020 The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

DOI: 10.3847 / 2041-8213 / abc6a2

arXiv: 2011.00324

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center runs the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

“요은 베이컨과 알코올에 대한 전문 지식을 가진 닌자입니다. 그의 탐험적인 성격은 다양한 경험을 통해 대중 문화에 대한 깊은 애정과 지식을 얻게 해주었습니다. 그는 자랑스러운 탐험가로서, 새로운 문화와 경험을 적극적으로 탐구하며, 대중 문화에 대한 그의 열정은 그의 작품 속에서도 느낄 수 있습니다.”